A Hitchhiker’s Guide to Asynchronous Programming#

Abstract#

The C10k problem remains a fundamental challenge for programmers seeking to handle massive concurrent connections efficiently. Traditionally, developers address extensive I/O operations using threads, epoll, or kqueue to prevent software from blocking on expensive operations. However, developing readable and bug-free concurrent code is challenging due to complexities around data sharing and task dependencies. Even powerful tools like Valgrind that help detect deadlocks and race conditions cannot eliminate the time-consuming debugging process as software scales.

To address these challenges, many programming languages—including Python,

JavaScript, and C++—have developed better libraries, frameworks, and syntaxes

to help programmers manage concurrent tasks properly. Rather than focusing on

how to use modern parallel APIs, this article concentrates on the design

philosophy behind asynchronous programming patterns, tracing the evolution

from blocking I/O to the elegant async/await syntax.

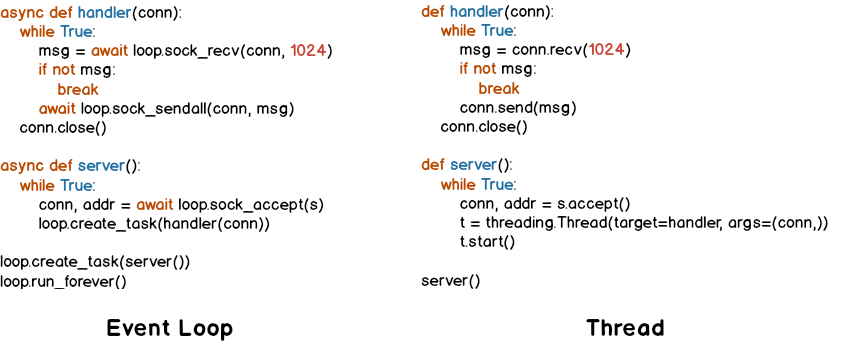

Using threads is the most natural approach for dispatching tasks without

blocking the main thread. However, threads introduce performance overhead from

context switching and require careful locking of critical sections for atomic

operations. While event loops can enhance performance in I/O-bound scenarios,

writing readable event-driven code is challenging due to callback complexity

(commonly known as “callback hell”). Fortunately, Python introduced the

async/await syntax to help developers write understandable code with high

performance. The following figure illustrates how async/await enables

handling socket connections with the simplicity of threads but the efficiency

of event loops.

Introduction#

Handling I/O operations such as network connections is among the most expensive tasks in any program. Consider a simple TCP blocking echo server (shown below). If a client connects without sending any data, it blocks all other connections. Even when clients send data promptly, the server cannot handle concurrent requests because it wastes significant time waiting for I/O responses from hardware like network interfaces. Thus, socket programming with concurrency becomes essential for managing high request volumes.

import socket

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM, 0)

s.setsockopt(socket.SOL_SOCKET, socket.SO_REUSEADDR, 1)

s.bind(("127.0.0.1", 5566))

s.listen(10)

while True:

conn, addr = s.accept()

msg = conn.recv(1024)

conn.send(msg)

One solution to prevent blocking is dispatching tasks to separate threads. The following example demonstrates handling connections simultaneously using threads. However, creating numerous threads consumes computing resources without proportional throughput gains. Worse, applications may waste time waiting for locks when processing tasks in critical sections. While threads solve blocking issues, factors like CPU utilization and memory overhead remain critical for solving the C10k problem. Without creating unlimited threads, the event loop provides an alternative solution for managing connections efficiently.

import threading

import socket

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.setsockopt(socket.SOL_SOCKET, socket.SO_REUSEADDR, 1)

s.bind(("127.0.0.1", 5566))

s.listen(10240)

def handler(conn):

while True:

msg = conn.recv(65535)

conn.send(msg)

while True:

conn, addr = s.accept()

t = threading.Thread(target=handler, args=(conn,))

t.start()

A simple event-driven socket server comprises three main components: an I/O

multiplexing module (e.g., select), a scheduler (the loop), and

callback functions (event handlers). The following server uses Python’s

high-level I/O multiplexing module, selectors, within a loop to check

whether I/O operations are ready. When data becomes available for reading or

writing, the loop retrieves I/O events and executes the appropriate callback

functions—accept, read, or write—to complete tasks.

import socket

from selectors import DefaultSelector, EVENT_READ, EVENT_WRITE

from functools import partial

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.setsockopt(socket.SOL_SOCKET, socket.SO_REUSEADDR, 1)

s.bind(("127.0.0.1", 5566))

s.listen(10240)

s.setblocking(False)

sel = DefaultSelector()

def accept(s, mask):

conn, addr = s.accept()

conn.setblocking(False)

sel.register(conn, EVENT_READ, read)

def read(conn, mask):

msg = conn.recv(65535)

if not msg:

sel.unregister(conn)

return conn.close()

sel.modify(conn, EVENT_WRITE, partial(write, msg=msg))

def write(conn, mask, msg=None):

if msg:

conn.send(msg)

sel.modify(conn, EVENT_READ, read)

sel.register(s, EVENT_READ, accept)

while True:

events = sel.select()

for e, m in events:

cb = e.data

cb(e.fileobj, m)

Although managing connections via threads may be inefficient, event-loop-based programs are harder to read and maintain. To enhance code readability, many programming languages—including Python—introduce abstract concepts such as coroutines, futures, and async/await to handle I/O multiplexing elegantly. The following sections explore these concepts and the problems they solve.

Callback Functions#

Callback functions control data flow at runtime when events occur. However, preserving state across callbacks is challenging. For example, implementing a handshake protocol over TCP requires storing previous state somewhere accessible to subsequent callbacks.

import socket

from selectors import DefaultSelector, EVENT_READ, EVENT_WRITE

from functools import partial

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.setsockopt(socket.SOL_SOCKET, socket.SO_REUSEADDR, 1)

s.bind(("127.0.0.1", 5566))

s.listen(10240)

s.setblocking(False)

sel = DefaultSelector()

is_hello = {}

def accept(s, mask):

conn, addr = s.accept()

conn.setblocking(False)

is_hello[conn] = False

sel.register(conn, EVENT_READ, read)

def read(conn, mask):

msg = conn.recv(65535)

if not msg:

sel.unregister(conn)

return conn.close()

# Check whether handshake is successful

if is_hello[conn]:

sel.modify(conn, EVENT_WRITE, partial(write, msg=msg))

return

# Perform handshake

if msg.decode("utf-8").strip() != "hello":

sel.unregister(conn)

return conn.close()

is_hello[conn] = True

def write(conn, mask, msg=None):

if msg:

conn.send(msg)

sel.modify(conn, EVENT_READ, read)

sel.register(s, EVENT_READ, accept)

while True:

events = sel.select()

for e, m in events:

cb = e.data

cb(e.fileobj, m)

Although the is_hello dictionary stores state to track handshake status,

the code becomes difficult to understand. The underlying logic is actually

simple—equivalent to this blocking version:

def accept(s):

conn, addr = s.accept()

success = handshake(conn)

if not success:

conn.close()

def handshake(conn):

data = conn.recv(65535)

if not data:

return False

if data.decode('utf-8').strip() != "hello":

return False

conn.send(b"hello")

return True

To achieve similar structure in non-blocking code, a function (or task) must

snapshot its current state—including arguments, local variables, and execution

position—when waiting for I/O operations. The scheduler must then be able to

re-enter the function and execute remaining code after I/O completes.

Unlike languages like C++, Python achieves this naturally because generators

preserve all state and can be re-entered by calling next(). By utilizing

generators, handling I/O operations in a non-blocking manner with readable,

linear code—called inline callbacks—becomes possible within an event loop.

Event Loop#

An event loop is a user-space scheduler that manages tasks within a program instead of relying on operating system thread scheduling. The following snippet demonstrates a simple event loop handling socket connections asynchronously. The implementation appends tasks to a FIFO job queue and registers with a selector when I/O operations are not ready. A generator preserves task state, allowing execution to resume without callback functions when I/O results become available. Understanding how this event loop works reveals that a Python generator is indeed a form of coroutine.

# loop.py

from selectors import DefaultSelector, EVENT_READ, EVENT_WRITE

class Loop:

def __init__(self):

self.sel = DefaultSelector()

self.queue = []

def create_task(self, task):

self.queue.append(task)

def polling(self):

for e, m in self.sel.select(0):

self.queue.append((e.data, None))

self.sel.unregister(e.fileobj)

def is_registered(self, fileobj):

try:

self.sel.get_key(fileobj)

except KeyError:

return False

return True

def register(self, t, data):

if not data:

return False

event_type, fileobj = data

if event_type in (EVENT_READ, EVENT_WRITE):

if self.is_registered(fileobj):

self.sel.modify(fileobj, event_type, t)

else:

self.sel.register(fileobj, event_type, t)

return True

return False

def accept(self, s):

while True:

try:

conn, addr = s.accept()

except BlockingIOError:

yield (EVENT_READ, s)

else:

break

return conn, addr

def recv(self, conn, size):

while True:

try:

msg = conn.recv(size)

except BlockingIOError:

yield (EVENT_READ, conn)

else:

break

return msg

def send(self, conn, msg):

while True:

try:

size = conn.send(msg)

except BlockingIOError:

yield (EVENT_WRITE, conn)

else:

break

return size

def once(self):

self.polling()

unfinished = []

for t, data in self.queue:

try:

data = t.send(data)

except StopIteration:

continue

if self.register(t, data):

unfinished.append((t, None))

self.queue = unfinished

def run(self):

while self.queue or self.sel.get_map():

self.once()

By assigning jobs to an event loop, the programming pattern resembles using

threads but with a user-level scheduler. PEP 380 introduced generator

delegation via yield from, allowing a generator to wait for other generators

to complete. The following snippet is far more intuitive and readable than

callback-based I/O handling:

# server.py

# $ python3 server.py &

# $ nc localhost 5566

import socket

from loop import Loop

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.setsockopt(socket.SOL_SOCKET, socket.SO_REUSEADDR, 1)

s.bind(("127.0.0.1", 5566))

s.listen(10240)

s.setblocking(False)

loop = Loop()

def handler(conn):

while True:

msg = yield from loop.recv(conn, 1024)

if not msg:

conn.close()

break

yield from loop.send(conn, msg)

def main():

while True:

conn, addr = yield from loop.accept(s)

conn.setblocking(False)

loop.create_task((handler(conn), None))

loop.create_task((main(), None))

loop.run()

Using an event loop with yield from manages connections without blocking

the main thread—this was how asyncio worked before Python 3.5. However,

yield from is ambiguous: why does adding @asyncio.coroutine transform

a generator into a coroutine? Instead of overloading generator syntax for

asynchronous operations, PEP 492 proposed that coroutines should become a

standalone concept in Python. This led to the introduction of async/await

syntax, dramatically improving readability for asynchronous programming.

What is a Coroutine?#

Python documentation defines coroutines as “a generalized form of subroutines.” This definition, while technically accurate, can be confusing. Based on our discussion, an event loop schedules generators to perform specific tasks—similar to how an OS dispatches jobs to threads. In this context, generators serve as “routine workers.” A coroutine is simply a task scheduled by an event loop within a program, rather than by the operating system.

The following snippet illustrates what @coroutine does. This decorator

transforms a function into a generator function and wraps it with

types.coroutine for backward compatibility:

import asyncio

import inspect

import types

from functools import wraps

from asyncio.futures import Future

def coroutine(func):

"""Simple prototype of coroutine decorator"""

if inspect.isgeneratorfunction(func):

return types.coroutine(func)

@wraps(func)

def coro(*a, **k):

res = func(*a, **k)

if isinstance(res, Future) or inspect.isgenerator(res):

res = yield from res

return res

return types.coroutine(coro)

@coroutine

def foo():

yield from asyncio.sleep(1)

print("Hello Foo")

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

loop.run_until_complete(loop.create_task(foo()))

loop.close()

With Python 3.5+, the async def syntax creates native coroutines directly,

and await replaces yield from for suspending execution. This makes the

intent explicit: async def declares a coroutine, and await marks

suspension points where the event loop can switch to other tasks.

Conclusion#

Asynchronous programming via event loops has become more straightforward and

readable thanks to modern syntax and library support. Most programming

languages, including Python, implement libraries that manage task scheduling

through integration with new syntaxes. While async/await may seem enigmatic

initially, it provides a way for programmers to develop logical, linear code

structure—similar to using threads—while gaining the performance benefits of

event-driven I/O.

Without callback functions passing state between handlers, programmers no

longer need to worry about preserving local variables and arguments across

asynchronous boundaries. This allows developers to focus on application logic

rather than spending time troubleshooting concurrency issues. The evolution

from callbacks to generators to async/await represents a significant

advancement in making concurrent programming accessible and maintainable.